St John-the-Baptist Catholic Church

Cnr Cowpasture Road and Mount Street, Bonnyrigg Heights

1879 Henry Bevington & Sons, 2m., 16 sp. st., tr.

(ex St John the Baptist Anglican Church, Hobart)

Trevor Bunning (Jan 2009)

The parish of Bonnyrigg Heights purchased the redundant organ from St John the Baptist Anglican Church in Hobart in 2006. This organ was the second to be erected in St John's and came from Henry Bevington & Sons, Rose Street, Soho, London in 1880. The organ was moved to a new organ chamber in a new chancel when the church was extended in 1902. The church closed some years ago and was converted into a dance school with the chancel area being converted into the owner's residence. The organ was in the owner's bedroom and was inspected by members of OHTA during the 2002 Conference, the owner then wishing it to be sold and removed. The organ was installed and restored at Bonnyrigg in 2007 by Mark Fisher of Pipe Organ Reconstructions.

Photo from OHTA website

From the Spring 2007 SOJ, Mark Fisher writes:

After 127 years in Hobart, this well known BEVINGTON & SONS organ has now been restored in Sydney and is currently being installed at John the Baptist Catholic Church at Bonnyrigg Heights by Mark Fisher of Pipe Organ Reconstructions Pty Ltd. It is well equipped now to begin a new life in completely different surroundings.

The organ was built in 1879 in London for St John the Baptist Anglican Church, Hobart and is BEVINGTON & SONS job number 1230. It was described by Bevington in December 1879 as "for St John's Hobart Town. - enclosed in a gothic screen case bracketed forward with richly decorated pipes of white ribbed metal."

The organ became redundant in the late 1990s after the church was closed and the building sold, complete with the organ. In April 2006, Fr Michael McLean and the Bonnyrigg Parish appointed Jim Forsyth as their consultant as they searched for a suitable pipe organ for the church. They approached Mark Fisher to find and recommend a redundant organ and he immediately suggested the Hobart organ. The church subsequently purchased the organ from the owners in Hobart and in June 2006, Pipe Organ Reconstructions went to Hobart to dismantle and pack the instrument into a container for its journey to Sydney.

The organ is of 2 manuals and pedals and contains 16 speaking stops, 3 couplers and 5 composition pedals. There are 777 pipes and the pedal organ contains a full length 16ft Open Diapason. A new floor has been built in the church for the organ and the area behind the organ completely insulated from sunlight and heat. The instrument is free-standing in the building and speaks clearly into a somewhat reverberant space.

The original hand-pumping mechanism is being reconstructed, so that the organ may once again also be hand-blown. The 31 façade pipes, made from 'white ribbed metal' - Bevington's specialty, have had more recent re-paintings stripped off and the still-discernible original design reproduced again. Two sections of the pipes, originally featuring bands of dull blue at the tops and two-tone grey at the mid-section, have now had those sections re-painted in shades of green to pick up on the church's interior window fittings and door frames.

The front casework of the organ has been returned to its original format. In 1903 the organ was moved to a new position in the church at Hobart and the side flats of the front façade and case were moved forward about 300mm to fit a new chamber archway. These flats have now been put back to their original position. This, together with other alterations made to the case at that time, has resulted in the need for a great deal of cosmetic surgery and reconstruction of some posts and other sections of the case, using matching timbers. In the process, the whole was stripped back to bare timber and re-stained and polished.

The 1903 organ bench was sold with some fittings with the church, but would have been unsuitable because, at the move, the floor at the console was raised nearly 200mm and the Pedal board and front case recessed into the floor necessitating a new bench at that time. In 2007, a new bench of European Oak was designed by Mark Fisher, in the style of another Bevington bench in England. This design features four turned columns on the bench which partner four columns around the console.

All painted sections of the organ's interior, together with the wood pipes, have been repainted in colours exactly matched to the original; even the lettered stencils on the floor frame, building frame and pipe racks have been faithfully reproduced to match exactly and these repainted directly over the original positions.

The interior metal pipework, made from an unorthodox high-tin alloy, peculiar to Bevington, is in an outstanding state of preservation and has been cleaned, with spectacular results. The original standard of workmanship, obvious in every aspect of this instrument, is typical of Bevington's superior quality, both in design and manufacture and features much that is never seen with any other builder. Expensive and very stable timbers were also used throughout and extraordinary lengths gone to in order to protect the bellows, windchests, frame, wood pipes and casework from the effects of the Australian climate. Restoration of the double-rise bellows reservoir and feeders, as well as the windchests was not begun until these had experienced the effects of a Sydney summer.

A new Ventus blower has been installed at the rear of the organ, together with its attendant blind valve, silencing box and muffler chamber. Because of Government safety laws, the organ has had to be located one metre away from the rear wall, to provide legal access to two emergency exits behind the organ.

Other work and some unhelpful alterations, carried out in 1903 by George Fincham at the time of the organ's move, were either reversed in this restoration or executed in a more suitable manner. Further work alluded to in writings since 1903 was found to be incorrect or wrongly assumed. Complete details of all work carried out during the 1903 move together with all details of the 2007 restoration will be given in a future issue of the Journal.

There is no doubt that this instrument, now free-standing, will provide a fascinating revelation into the work of Bevington & Sons that has not always been seen or heard in Australia.

The Bevington organ was opened on Sunday 18th March 2008 at a Solemn Pontifical Mass with James Dixon, conductor, and James Goldrick, organ. Kurt Ison played the inaugural recital the same afternoon, with associate artists.

The specification is:

| Great Open Diapason Claribel Horn Diapason Dulciana Principal Harmonic Flute Twelfth Fifteenth Swell Bourdon Double Diapason Open Diapason Bell Gamba Principal Fifteenth Cornopean Pedal Open Diapason |

8 8 8 8 4 4 2-2/3 2 16 16 8 8 4 2 8 16 |

TC C-B TC |

M W - stopped bass to TC M - shares stopped bass with Claribel to TC M M M M M stopped wood, separate slide M M - shares stopped bass with Bell Gamba to TC M - stopped bass to TC M M M W |

Mechanical action

Compass 56/25

3 composition pedals to Great

2 composition pedals to Swell

Hitch-down Swell pedal

Trevor Bunning (Jan 2009)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Photos above: MQ (Opening of organ 18 Nov, 2007) |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 photos above: Trevor Bunning (Jan 2009)

Photos taken by Pastor de Lasala 2007 (copyright)

A WORK OF ART RESTORED FOR A NEW START

ANOTHER BEVINGTON & SONS ORGAN FOR NEW SOUTH WALES

MARK FISHER WRITES

(Sydney Organ Journal, Autumn 2008)

HISTORICAL

The 1879 Bevington & Sons organ, opus 1230, formerly at St. John the Baptist Anglican Church, West Hobart, was blessed and dedicated at its new location by Cardinal George Pell, on Sunday 18 November 2007. The congregation of more than 1200, joined in the great occasion to welcome the organ at John the Baptist Catholic Church, Bonnyrigg Heights. Following a luncheon, Kurt Ison then gave the Inaugural Recital and Concert, ably assisted by Brett McKern, with soprano Jermaine Chau, trumpeter David Pye and violinist Sylvia Wong.

The latest addition to Sydney’s many historic pipe organs has been recently restored by Pipe Organ Reconstructions Pty Ltd., and is an excellent example of the successful relocation of a redundant instrument from elsewhere in Australia. Sydney lost its first and largest Bevington & Sons organ to come to Australia, in the fire which destroyed St. Mary’s Cathedral on 29 June 1865. The second, the 1888, 3/25 instrument remaining at All Saints Hunters Hill, is now joined by a smaller and older stablemate which, despite its size, is able to give a much better account of itself and its builder, by reason of a freestanding position in good acoustics. A further Bevington instrument, also for Sydney, was purchased by Pipe Organ Reconstructions Pty Ltd in 1995 and its restoration is now well advanced. The Bonnyrigg organ is a perfect example of the many hundreds of individually designed mid-sized instruments by this London builder that are still in use around the world. It displays every facet of Bevington’s superior quality in their pipework, windchests and action, as well as great skill and artistry in design, workmanship and finish. Many innovations employed in their work are not seen with any other builder.

Bevington & Sons, of Soho, London, built more than 2000 organs1, including a number of really sizeable instruments, in twenty-five countries as well as the UK. They understood the importance of reliability, using simplicity and long-lasting quality; and they paid very close attention to every detail of their work. This was particularly true of exported organs; firstly, to ensure a perfect condition on arrival and, secondly, to permit ease of assembly of their instruments, wherever in the world they arrived. All organs exported by the firm were in every instance most carefully packed under the strict supervision of the principals. Their reputation for consistent high quality and superior packing of organs sent overseas, led to the firm having, at the close of the 19th century, the largest export business of anyone in the trade2. Bevington & Sons sent organs to Africa, Australia, Belgium, Bermuda, British Burma, British Guiana, Canada, Canary Islands, Costa Rica, Cuba, France, Gibraltar, Hungary, India, Ireland, Italy, Jamaica, Mexico, Newfoundland, New Zealand, North America, Quebec, Spain, Sandwich Islands (Hawaii), and the West Indies.

Opus 1230, of 2 manuals and pedals, with 16 speaking stops and 777 pipes, left Bevington’s Rose Street Manufactury in Soho, London, at the end of November 1879, on board ship bound for Tasmania. It was described in a notice published in Musical Opinion of 1st December 1879 as “for St. John’s Hobart Town – enclosed in a gothic screen case bracketed forward with richly decorated pipes of white ribbed metal.”

From Bevington’s information sent to a New Zealand church committee in 187711, an instrument the size of the one for Hobart would have been be completed within four months. The firm’s yearly output around this time was 156 organs – or three organs per week.

Specification of the Organ

| Great Open Diapason Claribel Horn Diapason Dulciana Principal Harmonic Flute Twelfth Fifteenth Swell Bourdon Double Diapason Open Diapason Bell Gamba Principal Fifteenth Cornopean Pedal Open Diapason |

8 8 8 8 4 4 2-2/3 2 16 16 8 8 4 2 8 16 |

TC TC TC C-B TC |

M W M, sharing Stopped Bass* with Claribel M M M M M stopped wood, separate slide W & M M M, sharing Stopped Bass* with Open Diapason M M M W |

Mechanical action

Compass 56/25

3 Composition Pedals to Great

2 Composition Pedals to Swell

Mechanical action throughout

Hitch-down Swell Pedal

Flat Radiating Pedal Board

*Stopped Bass pipes on Great and Swell are not on separate drawstops, but draw automatically as required.

Ventus blower: wind pressure 70mm (2 ¾”)

The opening of the organ at St. John’s was written up in Church News; 1/5/1880, p71: “The organ has been erected in the church by Mr Wm Anderson3, of Melbourne, who speaks in the highest terms of the care and workmanship bestowed upon it by Messrs Bevington.” J. Finch Thorne, brother of E.H.Thorne (Organist of St. Anne’s Soho, London), supervised the installation and played the opening recital4. The organ stood, freestanding, at the east end of the north aisle, until structural problems in the east end wall of the church became evident in 1900. Finally, in 1902, the chancel was closed off and the east end of the church demolished. It was decided that the whole building could be improved if the chancel was extended further east, which would then allow the organ to be accommodated in a new chamber in the tower on the northern side5.

In 1903, George Fincham & Son, organ builders of Melbourne were entrusted with the job of taking down the organ, carrying out some alterations and re-erecting it in the new chamber. Fincham’s quotation for the work6 is as follows:

GEO FINCHAM & SON CORRESPONDENCE RELATING TO ST JOHN-THE-BAPTIST ANGLICAN CHURCH, GOULBURN STREET, HOBART, TASMANIA

Volume 19:

1 June 1903, p.355

Rev Mr Atkinson [presumably the Rector]

Double acting generators & Melvin pattern engine constructed in gun-metal throughout with patent starting dial at key-boards together with all necessary frames, trunking, regulating gear, &c &c £50:0:0

Melvin pattern engine as described above, with necessary connecting rod, regulating gear &c &c £35:0:0 Kindly note that this work is fully guaranteed & includes everything necessary, excepting only the plumbing work, meter, stop cock &c

8 July 1903, p.415

Colonel A. Reid, Frederick Street, Hobart

Re: Organ St. John’s Ch. Goulburn St.

Dear Sir:-

We have estimated the desired alterations to the above instrument as follows:-

To clean, remove & re-erect £30-0-0

“ Place feeders on frames, reverse same to suit blowing &

lengthen handle 18”, alter position of draw-knobs of Great

Open Diapason, Claribel, Principal & Twelfth also Swell

Double Diapason & Fifteenth, making draw in proper order £9-0-0

“ Provide 2 Composition Pedals to Swell together with

necessary action £7-10-0

“ Convey off two (2) pipes of Ped. Open to back of organ

& draw the stop on Bass jamb £2-10-0

“ Supply to the Swell : Gedact (or Stop Diapason) & Oboe,

together with supplementary sound-board, action, &c &c,

including necessary alterations to Swell-box £55-0-0

“ Reduce the power of the Great Gamba [sic] & Dulciana £2-2-0

To bring forward the side flats of Front in line with present

centre flat, altering side framing to suit &c £6-0-0

We cannot advise that the Swell Double Diapason be made available on the Pedal. The cost would not justify the alterations. It would be almost as expensive as a Pedal Bourdon

Provided the foregoing alterations + additions are carried out, the cost of cleaning & re-erecting organ (together with many minor details not specified) could be reduced to £25-0-0

The estimate for engine &c we have already supplied to the Rev. Mr. Atkinson, who has, we expect, handed the same to you.

We are

Dear Sir

Yours obediently

Geo. Fincham & Son

29 July 1903, p.452

L.V.H. Fincham and A. Ground to work on the job in Hobart

19 August 1903, p.490

Mr C. Nuttall (GF&S staff)

Engine + generators packed ready for shipment, there are 3 packages, generators, Clarionet, glue, collars & conveyance stuff, Engine bolts &c. Generator framing & trunk stuff, they will be shipped by the “Flora” leaving here on Friday at noon, this is a direct boat.

31 August 1903, p.515

Mr C. Nuttall

“…sorry to hear that the packing case was all to pieces”

The price quoted by Fincham to clean, take down and re-erect the organ was so cheap as to almost defy belief. It is not surprising, therefore, that the bulk of the work was executed in an unhelpful manner and certainly did not match the “care and workmanship bestowed upon it by Messrs Bevington.” However, it was also most fortuitous that some major alterations planned and quoted for above were, in fact, never carried out; much of the work attributed to Fincham at Hobart and reported by E. N. Matthews in her book Colonial Organs and Organ Builders (1969) is incorrect and has since been perpetuated in other publications for nearly 40 years.

E.N. Matthews’ account of work supposedly undertaken by Fincham in 1903 and 1905.

1880, two- manual organ by Bevington & Sons, London; 1903, organ moved to new position in church; alterations made to case and front pipes, position of draw-knobs altered, two composition pedals and cornopean added to swell organ; hydraulic blowing installed, by Fincham & Son. 1905, gamba removed from great and placed on spare slide in swell organ by Fincham & Son who later added pedal bourdon to organ. p199.

The original placement on the jambs of both the Great or Swell drawstops was never altered.

No additional pipes were added or transplanted on either the Great or Swell organs.

There was never a spare slide in the Swell.

The organ left London with all its pipes. All the engravings on the pipes conform exactly, no rack holes, hooks or stays have ever been touched and the organ specification was not reported as incomplete when it left London (which, in Bevington’s announcements it always would have been, with ‘prepared for’ slides indicated). Anyone seriously looking at the organ would note this immediately and also note that the Great ‘Gamba’ (sic), (actually the Horn Diapason), could never have been accommodated in the Swell. Likewise, the Cornopean was in the organ as delivered. By 1903 and 1905, the style of jeweller’s hand-engraving had long disappeared from Bevington pipework.

No Pedal Bourdon was ever added; and furthermore, two pipes of the Pedal were not ever conveyed off to the back of the organ. The stop labelled Bourdon in the swell is, in fact, Bevington’s original design wherein the bottom octave of the Swell Double Diapason (whose pipes are outside the Box) draws separately and is able to be independently played on the pedals through the Swell to Pedal coupler. Again, anyone examining the organ would work that out very quickly.

Work actually undertaken by George Fincham & Son in 1903.

[It is noted that Leslie V.H. Fincham and Alex Ground were clearly sent to Hobart to carry out this work, without any supervision from George Fincham, who would have been aged 75 at the time. Leslie was only aged 24, so he was still relatively inexperienced. The church people clearly wanted the organ in their chamber at all costs, so they and their architects must also share some of the blame for what eventuated.]

Specific work carried out by Fincham, to “clean, take down and re-erect in the new chamber.

The side flats of the front were brought forward to be in line with the centre flat.

Off-note conveyances to the side flats of pipes were altered and lengthened.

The uppermost octave and a half of the Great Horn Diapason and Dulciana were found to be tapped closed slightly at the footholes to reduce the power of those pipes. This supports Fincham’s proposal.

The Pedal Open Diapason drawstop was moved across to the bass stop jamb and placed between the two pedal couplers. It was made to work by an ad hoc movement, which cannibalised the former action parts.

Two composition pedals were added to the Swell division. The action for these, which utilised long backfalls and a heavy central beam, to enable the movement back to the Swell stop action, was crude and archaic in construction in comparison to the rest of the organ. Fincham did, however, have the foresight to copy the existing Great composition pedals, but did not paint them as had Bevington for the Great composition pedals.

It is almost inconceivable that the Pedal drawstop and its mechanism were moved, just to make way for the clumsy “Patent starting dial at the keyboards” for the hydraulic engine, which took its place. Whilst this and the engine were later removed, an equally hideous and oversize electric switch for the organ blower (no doubt to make the newly installed electric power as noticeable as possible) took its place until the restoration. The hacking away of the stop jamb, the key-bed in front of the stop jamb, and the cover plate had to be seen to be believed; and was a very vivid reminder of the uninformed culture of some in the past, that permitted this type of desecration. In altering the mechanism of the pedal drawstop at the bellows, where the movement travels through the front wall of the well, the leather gland was rebuilt on the inside of the bellows, where it is much more difficult to access for eventual renewal.

The exact work done to incorporate the operation of the feeders by the hydraulic engine is not known as, although the two original feeders were still attached to the underside of the double rise reservoir, the original pump handle and connections were long gone. Two wind trunks, obviously from an early date, were fitted to the rear of the reservoir and travelled down through the floor to the room underneath to where the hydraulic engine and then the electric blower had been. Fincham’s plan to lengthen the original pump handle by 18 inches to allow operation by the engine mechanism is difficult to verify, as there was no hole in the floor, nor any correct resulting alignment, obvious from such a position, for the connecting rod from the hydraulic engine. It seems to have transpired that new feeders, in reverse, on frames, were made in Melbourne and shipped, along with the engine and generator assembly ready to be installed, together with a (smaller) reservoir, under the floor nearer the engine; and the wind fed through the floor, via the two trunks, to the main bellows reservoir.

In planning the new space for the organ in the extended Chancel, it is also inconceivable (but probably, even today, a fair bet) that right on site they got it wrong; and some fairly serious surgery was then

necessary on the floor frame, building frame and the stunning casework, to squeeze the organ into the available space. This, for me, was the saddest aspect of our dismantling and gradual removal of the organ from the chamber; to realise the extent of butchery that had befallen the hidden sections of this work of art.

Loss and damage at the time of the 1903 move:

The top transom rail and the 9 decorated dummy-pipe panels from the treble end of the case, were dispensed with and were lost.

The rear right hand corner of the floor frame, building frame and case posts was removed and/or cut away so as to clear a wall; and some remains were re-fitted to allow them to be supported on a window sill.

The outside front case posts were cut off 200mm from the bottoms, so that they could sit on the higher floor of the new chancel, even though the whole of the rest of the organ was maintained on the original floor level.

The pump handle and connections, together with the tell-tale unit were discarded and were not in the organ.

The original bench was lost and/or discarded at the time of the organ’s move in 1903. The new higher floor, with the pedal board now set right into it, demanded a substantial alteration, or a new bench. At the time of the organ’s sale, no bench was present and none of the earlier ones could be traced.

Substantial areas of front casework had been damaged in the re-fitting to the new side flats position, as well as by extra cleats, screw and nail holes. The two main central upright posts had large holes cut out of them, at the point where the newly positioned impost rail now fitted into them. As more of the dismantling continued, I admit to being surprised and dismayed at just how much hidden damage was being uncovered.

The top 300mm of both the largest pipe of the pedal open diapason and the largest decorated dummy pipe panel had been cut away, so that they would fit under the sloping roof of the new chamber.

The organ subsequent to 1903.

By the 1930s, water damage over many years had affected the pallets and pallet-beds, which face upside down on the floor at the front of the pedal windchests, causing cyphers to some pedal notes. Charlie (Ivor) Matthews from George Fincham and Sons re-covered, in situ, the pallet beds with leather and fitted new felt as well as leather to the pedal pallets7.

Some weights were removed from the reservoir (although they still remained in the organ) to presumably drop the wind pressure, to overcome the lack of wind supply (at the correct pressure) from the very aged and undersized electric blower. The organ was under-winded as a result, and may never have sounded its true self from 1903, or at least in its latter stages of electric blowing.

The tops of many of the metal pipes, particularly those in the Swell Box became damaged over the years as a result of hastened tunings “on the run” from a difficult access position.

The surfaces of most of the naturals and sharps of the pedal board had been recovered in Tasmanian Blackwood.

The music desk had been broken at some stage and the underside of the console lid very badly marked as a result of organists trying to close the lid with the music desk pulled out and the clips still in the upright position.

The Swell Pedal hitch-down stick had been renewed, but was a very flimsy affair.

Water damage had also rotted away sections of the floor frame across the front of the organ under the new floor.

Many sections of the exquisite fret-work on the front case panels had broken away.

The façade pipes had been repainted. Firstly some sections were repainted (most likely by Fincham in 1903, where the top bands were touched up in a bright blue gloss finish paint, which stood out like a sore thumb); and then subsequently, all the maroon sections had been painted over once again in a very rough manner and areas of the bottoms of the pipes painted in what appeared to be ‘Silverfross’.

The church de-consecrated and the building sold

In the 1990s, the Parish faced ever increasing maintenance and major repair costs to the church building and, finally, the parishioners faced the inevitable. One said,” it is impossible for us to be objective about relinquishing the church we love”8. In December 1998, St John’s was de-consecrated and the building, complete with its organ, was sold. After a short period, the building was sold again in 2002 when the property was named Pendragon Hall. It was converted into a rather splendid B&B. At this time, I was able to establish contact with the owners and so began a close watch on the fate of the organ, which was subsequently listed on the OHTA redundant organ list. A number of prospective buyers of the organ were able to be kept well informed and in August 2004, a Victorian client flew me to Hobart, so that together, we might negotiate a sale with the organ’s owners. An agreement on price could not be reached and so the owners decided that they would keep the organ as an asset to the building.

In April 2006, Fr Michael McLean and the Bonnyrigg Parish appointed Jim Forsyth to act as their consultant as they searched for a suitable pipe organ for the church. They approached me to find and recommend a suitable redundant organ and, after examining a Sydney organ with them, which proved most unsatisfactory, I recommended the Hobart organ. In early May 2006, I began enquiries again with the organ’s owners, this time successfully; and on 23 May, the Bonnyrigg parish purchased the organ from its owners and entered into a contract with Pipe Organ Reconstructions Pty Ltd to fly to Hobart on the 4th June, to dismantle the organ and bring it to Sydney for restoration prior to installation at Bonnyrigg Heights.

Good News still present after 127 years.

The organ had remained completely intact apart from those very recognisable areas of human intervention,

Not one metal pipe had collapsed, not one knuckled mitre joint on the Cornopean resonators had given way or buckled and every pipe spoke, albeit a little underwhelmingly from under the dirt and lower wind pressure.

Every piece of the key and pedal action was present and showed minimal wear.

Only small areas of the stop action displayed any wear.

Apart from tuning manipulation around the tops, by hand and from rough coning, nearly every pipe was virtually undamaged,

The only pipe ear missing was that from a large façade pipe, another pipe, g44 of the Great15th had been replaced with a pipe from spotted metal. This pipe has been replaced with one of correct appearance.

There appeared to be very little, if any, splitting or cracking of the wood pipes.

The windchests, rack boards and stays, together with those off-note conveyances not modified by Fincham in 1903 remained in totally original condition..

All the Bevington ironware, apart from the pump-handle top rocking pivot and the two arms to the feeders was present.

Most of the builder’s paper labels – hand written with assembly positioning and/or directions – remained intact on various parts of the frame and case.

The only areas of the organ that required any reconstruction or repair work were those areas built or altered by Fincham in 1903.

Every single untouched piece of the organ remained in mint condition under the heavy layer of dirt, dust and cobwebs.

The Organ is brought to Sydney.

The organ was dismantled in three and a half days and, with local lifting help, packed into a 20ft shipping container delivered to the church on the back of a truck. After a long day’s packing, the container was sealed and driven by road to Burnie, thence travelling by sea to Melbourne and rail to Sydney. During the first stage to Burnie, the truck visited a weighbridge, where the weight of the organ was able to be established at 4.27 tonnes. On arrival at the manufactury of Pipe Organ Reconstructions Pty Ltd, the container was greeted by members of the organ committee from Bonnyrigg Heights who assisted in the unpacking. The organ was stored at the manufactory before and during the restoration to allow the wooden pipes, the windchests, rack-boards and bellows to experience a full cycle from mid-winter in Hobart to their first very hot and dry Sydney summer, before any attempt was made to restore them. Some splitting and cracking did occur over this time, all of which was able to be corrected as each part was restored.

So that an informed quotation and scope of work could be finalised for the restoration, the organ’s floor frame, building and case frames, case posts (where possible) and some case panels were erected, in order to properly detail the extent of repair required for these parts. Some sections had not been visible at Hobart, being hidden away out of sight in the organ chamber, or beneath new sections of over-floor; and only now was the full story of Fincham’s 1903 alteration work, able to be properly revealed.

THE RESTORATION

Timber for repairs and reconstruction.

Bevington used an amazing array of timbers in this organ and I was relieved that I did not have to chase supplies of too many of them, the reconstructing or repairing merely requiring the three pines that we had in stock. The timbers in the organ were; Douglas Fir, Yellow Pine, Sugar Pine, Scots Pine, English Elm, English Oak, European Ash, Canadian Rock Maple, Honduras Mahogany, Ebony , Sitka Spruce and Walnut.

The reconstructing of sections of the floor frame, building frame, case frame and front case posts was carried out using Douglas Fir (or North American Columbian), the same timber as Bevington used, stocks of which, dating from 1845, are held by Pipe Organ Reconstructions. Repairs to the Console and case panels were done from either 1926 Sugar Pine or 1845 Yellow Pine and Douglas Fir, whichever best matched the particular location. In many cases it was possible to closely match the grain. Bruising was ironed out and all timber parts were sanded. Mahogany for small repairs to the rack-boards and the reconstruction of the pedal stop action was sourced from remains of old derelict organ parts saved by P.O.R.

There are not sufficient quantities of English Elm available today to re-surface the pedal sharps and naturals in timber matching the original pedal board frame and pedals. European Oak was substituted and stained to match.

The new organ bench was designed by Mark Fisher from a photograph of the 1882 Bevington & Sons organ built for the music room at “Chartfields” near Sevenoaks in Kent9. This design was chosen, because it incorporated four pillars with capitals, which mirror the case pillars either side of the console. Again, European Oak was chosen and the colour and finish matched to the Pedal Board.

The broken music desk was reconstructed in English oak, to match the original.

The stop jambs were re-veneered at the front with two laminated thicknesses of English Oak and then re-drilled, because attempts to remove ingrained water stains, as well as invisibly fill the sections cut out at the bottoms of both jambs, did not enable the high standard of finish of the rest of the console to be matched.

Painting

From the 1870s, Bevington & Sons began to develop a system of colour coding for the internal sections of their exported organs, which made it easier for almost anyone in far flung areas of the globe to be able to quickly assemble their instruments, once unpacked, even though they had no earlier contact with the organ. This system of numbering and colour coding reached its greatest development in the 1880s (Waimate North 1885, Hunters Hill and Pontville 1888). Organs for the UK, Europe and even India and North America, were often erected by Bevington’s men, or agents who were familiar with the construction details of their organs. More often than not, however, there were few or no skilled organ builders to be found; and Martin Bevington’s scheme involving a more-than-usually careful division of the organ into separately packed sections, of a clear indexing system of colouring and numbering as well as the individual labels, was, at any rate sufficiently out-of –the –ordinary to merit favourable comment by ‘Lloyds of London’ It is quite surprising to walk into one of Bevingtons instruments from the 1880s and be confronted with all the colours, but it obviously made assembly much faster and easier.10

For this restoration, the various colours used by Bevington on the internal timber and ironwork were all exactly matched. This caused great angst at the local paint merchants, who were sometimes seen running as I entered the store, particularly as this was not the first time they have faced such challenges from me. Bevington’s colour shades, of course, were unique both to this builder and to this job, and sometimes even varied slightly throughout the organ as the paints were mixed as they were needed. Matching is made all the harder by the fact that the old paints were more like thin washes, rather than the full-bodied paint finishes of today. They were easily contaminated by age, wear and dirt, making them extremely difficult to match exactly, especially from the usually small areas found good enough to attempt a match. The grey of the building frame took more than two days to get right, because the computer kept picking up on one pigment which confused it and in other areas, the primer underneath influenced the shade. Eventually, the right shade was achieved with very clever mixing by hand. The maroon of the large wood pipes and swell box differed slightly to the maroon used by Bevington in the other instrument currently at the factory. The iron rollers in each of the three rollerboards were finished in black, as was the transverse axle used in the Swell to Great coupler, whereas ironwork used in the bellows counterbalances, the hand-pumping mechanism, the axles for the Swell Pedal movement, the composition pedals, together with a number of small iron parts throughout the organ was painted a very deep chocolate crimson, which I had not seen before.

With the exception of the Pedal Open Diapason pipes, the manual windchests and the stop and key action components, all timber in the organ had been primer undercoated, even if it was then finished with another colour. Large areas of the organ remained with just this primer coat, which was applied as parts were constructed, because even the inside and unseen areas of the mortice and tenons of the framework were meticulously primed. When the organ stood finished in Bevington’s works, the other colours were painted on the various parts, so that when the organ came apart for packing, the pink primer was still visible underneath where something else had been attached on top. The manual wood pipes were made, then twice sized on the insides, painted maroon on the outside, inscribed with their note, rank and job number, cut up and voiced and then had unprotected areas such as the mouths finished again with primer – over the inscriptions. Following this the caps of the larger similar ranks were then stencilled in Indian ink so as to identify the stop.

This extra preparation was described by Bevington11: “All the framework and the inside of the case and bellows are to be specially prepared, so as to effectively resist damp.” This extra work can be seen on early instruments (Launceston 1874), (Hobart 1879), (Christchurch and Dunedin 1877 and 1880) in Australia and New Zealand, but is partly absent on later instruments (Hunter’s Hill 1888), (Pontville 1888), (Waimate North 1885) and does not appear to occur in any of the instruments built for the UK. One wonders why the builders considered Tasmania and New Zealand to be damper than the UK. It probably was more likely associated with the special treatment generally afforded exports, especially to the tropics, but not limited to it. It is also possible that this extensive preparation was deemed too expensive and time consuming to continue.

The various structural sections of the organ were originally marked with large stencilled letters, to distinguish them thus: A – Floor Frame, B – Building Frame, C – Case Frame, D – Pipe Stays. Before any repairs or repainting was carried out, these letters were copied exactly and new stencils made for them. The positioning and angles of the letters were also accurately plotted.

The restored and reconstructed timber sections were fine sanded, extraneous holes were filled, and all areas to be primed again were masked off and painted. Grey sections were then carefully repainted overall or up to the primer edges and finally, the stencilled letters were painted in their exact pre-determined positions.

Casework

The beautifully proportioned casework has come back to life now that the side wings have been moved back to their original positions. I was lucky to have a c.1880 photograph of the organ, so I knew what a huge difference it would make to return to the 1879 layout. The heartaches of reconstructing some of the case and frames have been amply rewarded. The posts fit into the floor frame, which guarantees their accurate positioning. The floor frame protrudes slightly from all around the organ and in a real ‘first’, even has a section which supports and, via dowels, accurately positions the pedal board. There is a great amount of refined architectural detail on the case, with the panels all simulated so as to appear to be knocked together and pegged. Elaborate fretwork fleur-de-lis adorn the tops of the front panels across the organ and these are backed with scarlet cloth. The case posts, and front transom rails all fit together tightly and are held with tapered wedges.

Large oversized hinges, forged from black iron, adorn the console lid whilst the bracketed-out section of the case above is supported by four turned columns, with capitals of contrasting colour each side of the console.

The console, key cheeks, music desk and stop jambs are of French polished English Oak. The key surfaces were recovered in the material which is reserved normally for use for the naturals of Concert grand pianos. Two damaged Swell key arcades were replaced in the original material; and oval front pins for the keys were fitted in Hobart at some stage and hammered in very unevenly without removing or supporting the key frames!!! These were fitted properly and the keys made to work smoothly.

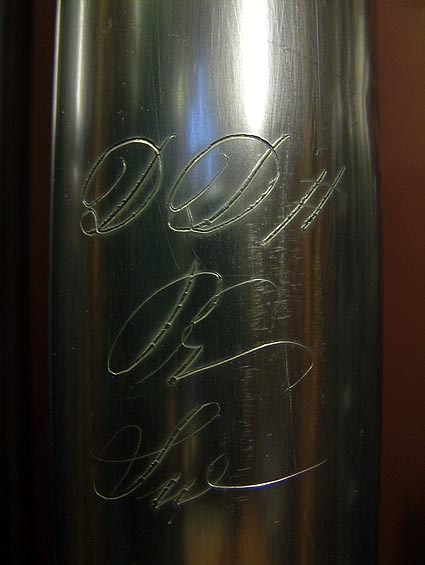

The gold leaf stencilling of the builder’s name was re-done by Erica Harrison to great effect. This was made exceedingly difficult by the fact that a lady organist had brazenly written her name heavily with a ball-point pen, into the name board, partly under the music rack; and this had to be removed and the surface rectified without obliterating all traces of the lettering, so there would still be a reference from which to work.

A new cover plate beside the treble end of the keyboards was made to replace the one butchered in the installation of the hydraulic engine.

All the case panels survived, but some were badly water stained and nearly all were heavily impregnated with nail and screw holes from the move of 1903 and subsequent fastening of electrical wiring – some quite recent. The bass end side panel was completely hidden from view behind the row of Pedal Open Diapasons and against the eastern wall of the organ chamber and no idea of its presence was had until the big pipes started to come out. This side panel was heavily covered in graffiti (the marked dates of which abruptly ended in 1903), some which was quite heavily carved into the panels, others written deeply with pencil. The whole timber surface was badly marked, so at the time of restoration, the decision was made to simply clean up the panel, leaving whatever graffiti survived. It now forms a very integral part of the organ’s history from its first 23 years.

As previously mentioned, the painted dummy-pipe panels and transom rail from the right hand end were lost in 1903. It is now hoped that the parish will proceed in due course to have these reconstructed.

Façade Pipes

As with nearly all of Bevington’s instruments from that period, the beautifully decorated façade pipe-work was an integral part of the overall stunning appearance of their organs and almost every one of their new instruments erected around the world gained special admiration for the colours and appearance of the facade. This important aspect was entrusted to William Lamb, specialist painter and gilder, of Margaret Street, Oxford Circus, who also did the work for nearly all the London organ-builders.

For their instruments, Bevington used, to great effect, the contrast between the bright tin-like appearance of his unique white ribbed metal and the coloured patterns on the pipes. In many cases, as with this instrument, the bright metal showed through gaps in the patterns of the colour. Trying to rescue and restore that appearance was rendered impossible, because these exposed bright sections had, at Hobart, eventually dulled off somewhat; and had all been painted over with silver paint. I tried every method to attempt to carefully strip off that silver paint without marking the metal or damaging the original outlines of the decorations, both on the lower sections of the feet and also the swirling patterns which showed through the main decorated areas. I was dismayed to eventually realise that removal of the silver paint was not going to be possible, without severely compromising the fine ribs on the surface of the metal. At this point I discussed my whole plan for the façade pipes with my specialist painter, Erica Harrison and we agreed that to match the surroundings in the organ’s new home, we would introduce shades of green already used by Bevington on the wooden dummy-pipe panels at the treble end and in others of their organs. The only workable solution that also looked attractive was to introduce the pale green into the swirls, where the silver had been, re-paint the top blue bands in dark green, change the midway band from grey with white markings to dark green with light green markings. The bottoms of the pipe feet were re-done in a much higher grade of silver paint, tinted to look as much as possible like the’ white metal’ of the pipes.

The roughly-painted most recent top coat was washed off all the pipes, using (of all things) Methylated Spirits. This instantly revealed the finer details of the original decorations and colours. After a thorough cleaning, the pipes were all repainted exactly over the original designs. The dummy-pipe panels at the bass end were in a state of some decay, because of the delicate nature of the paint as a result of prolonged damp. Erica advised that none of these would survive the first Sydney summer and her assumption proved correct with paint lifting and flaking off. Her recommendation was that all be firstly photographed, then each shade of colour carefully was recorded, each stencilled pattern then traced and its position recorded, after which, all the panels would be stripped and sanded back to bare timber. This done, the panels were then primed and the whole exercise of repainting commenced. The inclusion of these unusual panels, in an organ of this size, adds yet another touch to the restrained high ‘class’ that this instrument exudes.

The 31 pipes in the organ façade are from the Open Diapason and Dulciana, with two non-speaking pipes added in each of the outside wings. The wooden side dummy-pipe panels simply rack in to the side casework and disguise a wall of Pedal pipes.

Interior Metal Pipes

The unorthodox composition of Bevington’s pipe metal, peculiar to the firm, was frowned upon by many because it was not the supposedly highly valued spotted metal (45-55% tin-lead) which quality was immediately obvious from the appearance of its spots. Bevington’s metal was particularly hard and heavy – and the polished pipes glow with the warm colour of tin – the most prized of all pipe metals. The secret was the inclusion of antimony and copper in his high-tin content metal, which always attracted shrieks of derision from the purists. After 128 years, though, the quality and strength of this metal leaves all but the very best of spotted metal examples for dead. Not one pipe in this organ showed any sign of fatigue and, after cleaning, they look like they were made last week. Other organ builders also included pipes of plainmetal or black metal with zinc used for the pipes longer than 4ft. Bevington would have none of this. His metal flue pipes and reed pipes (even the reed blocks) were all of his own amazing metal. The longest 8ft pipes of the Open Diapason and Dulciana are exceedingly heavy and require two men to get them airborne and into the façade. All interior pipes have had the metal planed on both sides, so that the striated (“ribbed”) effect is reserved for the façade pipes (and their off-note wind conveyances). Bevington’s soldering size was a pinky-cream colour.

The names of the rank and the note are beautifully hand engraved with a jeweller’s tool and exhibit great flourishes, which further add to the uniqueness of this instrument. The organ remains cone tuned and, when the pipes were all rounded out at the tops, handfuls of octaves were in tune. By the ‘dead-length’ cutting of the pipes, it was easy to establish the correct pitch and pressure, without resorting to any pressure gauges or tuning aids. Because of the accuracy of this method, I had been able to determine that the tops of the Horn Diapason and the Dulciana must have been softened by regulation at the toe-holes, before I received John Maidment’s confirmation that Fincham had indeed carried out this work. Again, because the pipes were almost in tune before I began any fine tuning, it was easy to determine which way Bevington had faced the pipes on the windchests. Pipes that were too sharp (and which I refused to flatten before I tried every known measure to overcome their being sharp) immediately went into tune when they were rotated to face another way. Likewise, pipes that were flat were rotated; and went into tune. This gave me a further really good insight to the Bevington ethos of how best the pipes were positioned in order to reduce the chance of their being damaged, especially those across the rear of the Great windchest closest to the Walkway.

The treble pipes of the Twelfth break back to 8ft pitch at g#45 and the pipes of both 15th ranks break back to 4ft pitch also at g#45. This unusual arrangement is virtually undetectable when the stops are used in combination and in solo effects using, 8’ and 2’ or 8’ and 2 2/3’; the breaks are cleverly managed through the voicing and regulation of these small pipes. A big advantage is that, by being larger pipes, these trebles are not as vulnerable to sustaining damage from coning.

The Bell Gamba and the Horn Diapason.

These two remarkable stops, both similar in construction but of widely different scale, were favoured by Bevington & Sons and remained their ‘specialties’, long after everyone else had forgotten they even existed. It is certain that the extreme accuracy, with which they had to be made, was the reason they were quickly omitted by others, long before fashion might have dictated it. The tone of both stops has evoked high praise, from organists and others, who are astonished by their sound. The Horn Diapason (in earlier years, Bell Diapason) is of significantly large scale, very amply winded, as opposed to the Swell Bell Gamba (also a confidently speaking rank, which I had known for 35 years at Hunter’s Hill) The cylindrical pipes are surmounted by an upwards facing cone on a tube, the outside diameter of the tube being an exact fit inside the pipe body. In the organ, these pipes with their bells certainly command attention and are the subject of much discussion. The cone assembly is able to be moved up and down to enable tuning. The sound is very distinctive and unlike anything in a modern organ. It is a far cry from the normal (and slotted) string-toned pipes of similar scale which prevail with most builders. This form of pipe was first seen in England in 1851 as ‘Flute a Pavillon’ in an organ by Ducroquet at the Great Exhibition at Westminster; and Bell Diapasons and Bell Gambas were in use in 1858 by Bevington.12

The Double Diapason

Indicative of nearly all Bevington & Sons organs of two manuals or more, is the Swell Double Diapason, formed from open metal pipes of medium scale from middle c upwards. They sing and display a beautiful flood of slightly stringy tone. The octave below middle c is composed of small scale stopped pipes in wood, skilfully voiced – the transition from wood to metal being virtually undetectable. The bottom octave of the ‘Double’, was composed of Bourdon pipes, and always mounted outside the Swell Box. Being softly voiced, they allowed the sound of this stop to rise through to middle c, where it came into its own. This enabled a dignity and sense of restrained power, which was not muddy, when the stop was played in combination, particularly in the left hand. This stop far exceeds the results from a manual Bourdon and once it is joined by the fiery Cornopean, immediately stamps this instrument with the unmistakeable Bevington sound. Similar sized organs from Hill, Walker and Willis never achieved this grand refinement.

The Dulciana

It has long been my view that most builders gave up on the Dulciana, or never understood what they were trying to achieve. Walker’s Dulcianas were very small scaled and rarely went below tenor C. William Hill’s Dulcianas were slow and clumsy in their speech and tone; and, in zinc for the lowest 12 notes, murderous to get to speak correctly in the bottom octave. Many builders used beards or other methods - I have even seen slots employed. It was Snetzler who brought the Dulciana to England in 1754 and his use of fenders and ears on pipes throughout the rank suggests that he viewed the stops as quiet strings, similar to those of the southern German organs. However, Snetzler’s pipes were made with a slight outward taper (as a Dolce), a fact that Hill seemed to have conveniently forgotten in his attempted claim to continue the Snetzler ‘tradition’. It was Samuel Green (1740-86) who realised the Dulciana’s shortcomings in the dry English acoustics of the smaller parish church and thought of it as too quiet to be effective in large buildings. He treated his ranks as echo diapasons and made the pipes cylindrical13. This is the style that Bevington preserved with great effect. The basses purr right down to bottom C and the whole stop is devoid of any fizz or struggling speech. They just play. The basses are larger scaled than Hill but have low mouths – a recipe for success.

The Cornopean

This is an exciting example of Bevington’s later developments of their reeds after c.1876. Of greater power than Hill and similar power to Walker, it quickly stamps its identity on the full organ sound. With the Swell Box shut, it can be used as an oboe. The pipes are large scale with the resonators cut to dead length with no regulating slots fitted slightly down from the top. The open shallots are slightly tapered with the tongues in hard brass, lightly curved. The sound is prompt and fiery.

The Diapasons

These are all of quite large scale kept bright right up into trebles, with wide mouths and moderate nicking. The metal is kept thick and the pipes highly polished. The tone of the large scaled Open Diapason is surprisingly cello-like and there is far more harmonic development than any Hill stop of that name. This is more a product of the pipe-metal differences rather than voicing. All toe holes are nearly fully open and the pipes are amply winded. Generally, the languids are set higher and the mouths more forward than with Hill. The pipes are all cut to dead length and only slight coning is required on some pipes. All pipes sit firmly, without any movement, in the rackboards; and each has ample speaking room.

The façade pipes are tuned by means of two door-like flaps which open or close in front of the tuning slot and by this means these large pipes can be easily tuned from the passageboard.

The Wood Pipes

These have been meticulously made from pine. They are not dissimilar in appearance to Hill pipes, but give the impression that they are even more accurately made. The stopped pipes are strengthened around the top edges with calico. All have been twice sized on the insides. The outsides of pipes larger than 2ft in length have been first primed with the pink paint and then painted in the finished coat, whilst the treble pipes of the Claribel, from middle C, are of a hard, clear pine, twice sized. The stopper handles are turned in the very distinctive Bevington style (which was introduced in the 1850s) and the stoppers tune a good distance down from the top of the pipes. As mentioned previously, the pipes were obviously voiced and inscribed with their rank, note and job number before they were primed and painted.

The pipes of the Pedal Open Diapason form a majestic stop with a big sound and prompt speech. Made from first class pine, the largest pipes are remarkably light, compared to other builders’ pipes, making them just possible to be carried by one man. They are well bellied and have separate mouths attached. The large pipes have short feet with a regulating slide-piece, which can be pushed in or pulled out to vary the wind supply. Pipes in the bottom octave have been cut ‘dead to length’, whilst pipes from 8ft C have tuning flaps of the strong pipe metal fitted to their tops. Even though of a good scale, the caps of the Open Diapason 16ft are marked “Small.” The pipes are not quite as large in scale as Hunter’s Hill, but very prompt in speech and kept full and bright right to the top note.

The stoppers of pipes down to CC are covered in leather, whilst the pipes of the 16ft octave of the Swell Bourdon basses are covered in ‘swansdown’. This latter material was in almost perfect condition after 128 years, but was renewed again, as the old coverings had been removed before I realised what it was.

The Flutes

The Claribel produces the tone which made Bevington famous for this stop. It is pure liquid gold. The medium scale open wood pipes are exquisitely made and are tuned with metal tuning flaps. The Harmonic Flute (ten C) is larger scaled than most, harmonic from middle C and the sound rises in the treble. It combines beautifully with anything else on the organ.

The Stop Action

Bevington’s stop actions of this period were all of wood. Trundles of mahogany hold exquisitely turned and fitted arms of Canadian rock maple, which are not just drilled through the trundles, they are let in. An action such as this is completely devoid of the rattling clunks of the iron trundles by other builders. Bevington’s use of high class wood turners continued from around 1860 to after 1905. The organs were scattered with beautiful small timber parts and the precision and finish of these rang out ‘best quality’. It is obvious that, as organ-builders, they went out of their way to present the most artistic looking as well as functionally reliable and simple mechanisms. Most unusual, was the ‘draw’ of the stop knobs at the console which was 2 inches, when Hill’s was 4 ½ to 5 inches and Walkers were sometimes 6+ inches. Of course the minimum draw can be traced back to the superior quality and accuracy of their windchests.

In this instrument, the movement up to the windchests is via splayed backfalls – in larger organs or those with greater height to traverse, the action was by rods and squares, again, all in wood. Because of the great accuracy with which the stop action was made, clearances between adjacent actions may be kept to a minimum without sacrificing the ability to get at anything.

The trundle frames are made from European Ash and are fitted together with almost invisible dovetailing. The composition pedal fan frame is again from Ash with heavy horizontal trundles also of Ash, with the turned arms of Canadian Rock Maple fitted into them. The outsides of the fans are iron rods passed through holes drilled into the arms. These rods bear upon the blocks on the traces which allow a combination to be drawn.

The opportunity was taken, whilst the organ was apart, to manufacture a new composition pedal action for the Swell to replace the ungainly and out of character mechanism which was added at Hobart in 1903. I manufactured a new action which replicates that of the Great, using parts from Ash and turned Rock Maple. Having had the opportunity to reproduce Bevington’s mechanism, I more than ever appreciate the time, effort and accuracy that was required in their manufacture. Instead of two very long backfalls to transmit the movement from the front of the organ back to the Swell stop action, I introduced iron rollers with arms, in the same style as at Hunter’s Hill.

The ebony stop knobs on this instrument are not of the usual Bevington profile, something that puzzled me until I first set up the stop jambs at the factory. The reason that the music desk had been previously broken and the brass clips had been broken off after they had dug many times into the closing lid, was also the reason for shorter stop knobs. There was little or no clearance when the lid shut. I have not made clips for the new music desk and do not intend to fit any. So far, there have been no problems with music not staying put.

All the stop knobs, stop labels and lettering had been beautifully preserved, so very little was required to be done on them, besides polishing. The first letter on each label is in red, the rest black.

The stop jambs, each complete with its drawstops and trace rods were assembled as one unit and that was obviously how they arrived from England - an example of some pre-assembly work packed and sent as one unit. Each jamb was pushed into position from the front, from their position in the console. The unusual order of some of the stops on the jambs is deliberate by Bevington and is the only way that allows all the stop traces to be reached inside through the front of the console for connection of the Great stops to the arms of the stop action trundles. For similar reasons, the Swell drawstops are laid out in the only order in which it is possible to access each one for connection to the Swell stop trundles. Fincham’s quoting in 1903 to move the positions of individual drawstops would have proven impossible. Judging from the condition of some of the front connecting pins inside the stop jambs, I would say that an attempt was made and then abandoned when the true position became known.

The Key Action

The Great key action is by very long rectangular stickers of Sitka Spruce (a system which is frowned upon in all good organ building books).The stickers work via splayed backfalls to the Great pull-downs. These backfalls and their beam are from mahogany and were probably the single most impressive item in the organ. The amazingly accurate and well fitting movements were almost impossible to comprehend from an era so long ago. The twelve bass notes of the C# side were activated by shorter stickers and a small roller board above the keyboards. Stamped on the roller board is the Opus Number (found in this position in all Bevington organs).

The Swell key action is via short stickers to a square beam, thence by horizontal trackers to a rear square beam, from where the trackers pass via a conventional roller board on their way to the Swell pull-downs. This action through to the rear square beam, which also included the small Great roller-board, was another of Bevington’s pre-assembled units. The whole assembly was able to be placed in position through the space in the casework above the keyboards with no more than 4mm to spare, just as Bevington designed it to be.

A screwing adjustment, for raising or lowering the key height of the Swell keys, was introduced to each end of the rear square beam, so as to simplify any adjustment of the beam during Sydney’s big seasonal changes. The Great key action is readily accessible for key adjustments.

The Swell roller frame, containing rollers of two different diameters for long and short rollers, actually dovetails into each side of the building frame from above, so as to sit under the Swell windchest and this had to be fitted in place before the windchests were installed. This roller-board acts as a very strong horizontal brace for the building frame. The arms were re-bushed in kangaroo skin for very long wear and new pins, some slightly oversize, were fitted to the rollers to take up any wear and sloppy movement.

With the exception of the lower wires for the Pedal pull-downs, all the tracker bindings and original tapped wires were preserved, as they were in perfect condition. These pedal wires had suffered greatly from previous water damage, at the windchest, so all were replaced.

Henry Bevington, the founder of the firm at the end of the 18th century, quickly established his name for lightness and accuracy of his actions and for the reliability of his windchests. His men were sent to other organ builders to initiate them into the ways of good windchest manufacture14. One hundred years on, Bevingtons had lost none of that art and luckily didn’t take too much notice of organ-building books. The key action at Bonnyrigg is superbly precise, and not heavy, even though organs of only slightly larger specifications were given relief pallets. The whole key and pedal action is laid out in this organ with clockmaker’s precision.

The Pedal Action is via a large transverse roller board to the pedal chests which sit at ground level on both sides of the organ, with the pallet boxes at the fronts of each chest. The roller arms, at the outsides, protrude through the back of the roller board and pull up to open the pallets underneath. The action is virtually noiseless, a very dramatic change from the majority of pedal mechanical actions.

It is in the Pedal Coupler Action that, once again, Bevington excels; and this movement remained in use exclusively by the firm, until they seem to have abandoned it around 1902. The Pedal roller-board and both sets of splayed backfalls for the manual to pedal couplers each had their own trackers passing down to the pedal board. These trackers passed through individual holes in each pedal and screwed into a piece of thick leather, which was fastened to the underside of the pedals. Thus to adjust the trackers for any note of either the pedal action or the couplers, you simple turn the individual tracker one way or the other. The method is so simple, so quiet and so reliable, that it is incomprehensible that it was not taken up by any other builder.

The twenty-five note Pedal Board is flat and radiating. Unusually, the guide pins are from iron and, therefore had not worn at all. The pedals were sprung at the front with conventional springs, but fitted far enough into their guide holes in the pedal frame, that they had not worn the timber away, nor broken free of the hole.

A most extraordinary discovery was Bevington’s original method of providing a bearing surface between the pedals and the iron pins. At the position of the pins, the pedals had two horizontal ½” holes bored right through, one near the top edge, the other near the bottom edge. Into these holes were affixed hard cork dowels, which protruded sufficiently each side of the pedals as to provide a good bearing fit, with no side movement. These cork pieces had long since been cut off flush with the pedals and the more conventional felt and leather wrapped around the pedals, to provide the bearing fit. I experimented with different forms and quality of cork that was available, but sadly, had to abandon my hope to re-instate Bevington’s system. Sufficient good quality hard cork in the form that I wanted is no longer available.

The Double-Rise Bellows

Bevington’s preference for large reservoirs is certainly borne out here. The double rise unit, 2.16m x 1.53m, has the two unequal-sized original feeders attached and the hand-blowing system is being reconstructed. There are four counter-balances and these are ingenious in design, by having the bars joggled at their centres and dog-legged at their ends, so the units are kept away from the bellows itself and there is no chance of scuffing the leather. The total weight on the bellows top plate is 124Kg.

There is no large exhaust valve on the top of the bellows as a safety overload protection when hand blowing the organ; rather, two internal ventils are opened, when the bellows rises above its full height, and the extra air from the feeders is re-directed down again into each feeder. I have never seen this feature on any pipe organ, and would love to know who thought it up. In other words, when the organ is hand blown, excess air when the reservoir is full, is simply fed back into the feeders and there is no usual escaping air sound; the air is simply being pumped around in circles until the reservoir drops on demand of more wind for the organ.

At the time of restoration, another safety valve was built into the inside of the reservoir, which acts for the electric blowing. When the full bellows rises beyond a certain point, this valve is lifted and it exhausts the overflow air out through the side of the bellows. This valve was constructed in this fashion, to preserve the top plate of the bellows free of any visible exhaust valve.

The stop action for the Pedal pipes passes through the front of the bellows ‘well’, via a leather gland; and by a system of spring-loaded movements, two large ventils are opened on the inside of the bellows, which then allows air to be passed into the two pedal windchest pallet-boxes via short trunks.

The new pumping handle is supported at its fulcrum point by a post attached to the floor frame and screwed to the side of the reservoir. It is topped by a thick cast iron plate in which two V shaped holes have been drilled. Into this rests the pump handle, supported by a bracket containing two tapered dowels which pivot on the bottom of the holes – as in a jewellers’ movement. The exterior section of the handle passes through a slot in the rear right hand corner of the case. This visible section is being made removable when not in use.

This jewellers’ movement was even further improved in later years, as the remains of the mechanisms at Hunter’s Hill (1888) and the Milford (UK) (1905) organ at our factory illustrate.

Bevington’s tell-tale units were separate glass-fronted boxes, in which a white-painted weight moved up and down on the end of a string originating from the bellows. These units were viewed through a nicely cut slot in the casework near the pump-handle. It would appear from photographs, that tell-tales were rarely fitted at the console as well – an exception being at Ballybrack, Ireland c.1860. Both the units from Hunters Hill and Hobart are long gone, but I was lucky to be able to unearth the original one from Launceston from under the organ, after I went looking for it. It emerged filthy dirty, but I knew instantly what it was. I photographed it well and it will be reproduced here at Bonnyrigg.

The Windchests

The Great and Swell windchests are constructed of Honduras Mahogany throughout. They are extremely accurately made and feature brass pallet springs and large brass screws for the pallet box doors. The pallet beds are covered in fine leather and the pallets have now been re-covered with thin felt and leather to assist them in the difficult Sydney climate. The felt was kept deliberately thin so as minimise any ‘pluck-travel’ with the pallets, which would have spoilt the original feel of the action. The original Swell pulldowns were re-used but new pull-down wires have been fitted to the Great; and these all pass through their original brass register plates.

The introduction to the Sydney climate meant some minor splitting of the tables occurred, as was indeed expected. The Great windchest had been subjected to water damage, as had the Pedal windchests, the stop jambs, the Swell keyboard, the Case and the Floor Frame. The splits in the table were secured with screws and dowels, the splits filled and all sealed again with hot glue. The Swell windchest was less affected, but still had the same remedial treatment, where required. The front-and-back facing Pedal windchests, of Scots Pine, had split in several places on top and underneath, across their internal conveyance grooving. The damage to these was however, more easily rectified. The upside-down pallets were re-leathered again in felt and leather and the pallet beds were recovered in leather. New pull-up wires were provided.

The Great and Swell windchests featured another of Bevington’s clever inventions. The operation of the dedicated drawstop slider for the Stopped Bass pipes was ‘blind’ and not activated by a drawstop at the console. A small adjustable counterweight on a horizontal axle connected to the Stopped Bass slider, on each windchest, automatically drew this slider when any or all of the tenor C stops activated it – Horn Diapason and Claribel on the Great, Open Diapason and Bell Gamba on the Swell. This ingenious device overcame the problem of having more than one slider each communicating wind via channels in the toeboard to the one set of pipes. It also meant that the Stopped Bass slider and pipes could be placed at any convenient position on the toeboards and windchest, not necessarily next to those ranks with which it played.

The Swell Box

The rectangular Swell Box, with a roof sloping towards the rear (to clear the sloping roof of the side aisle at the organ’s original position), sits with dowels onto a separate horizontal frame, which itself is easily located on the top of the windchest. This makes the assembly of the Box much easier. The panels and roof of the Box are thick pine, but not of great weight, so that lifting the individual sections is not tempting fate in the organ. Messrs Hill, Walker, Willis, Nicholson, Richardson, Fincham and just about every other organ I have worked on would have done well to examine Bevington’s methods here. The shutters are unusual in that they overlap each other, like a clinker-built boat. This gives a better seal, a much improved crescendo and a better feel to the weight of the Swell Pedal. Bevington did not always use this system, though, and seems to have phased it out by 1885. The one disadvantage of the Clinker-style shutters is the extra overlapping intrusion to the restricted space on the central passageboard. The shutters here open to about 80 degrees, so that full swell is completely unimpeded. With the box shut the sound is well damped.

The four lowest pipes each of the Stopped Diapason Bass and the Principal 4ft are on a front-to-back facing toe-board in the centre of the Swell Box and played by extra pallets in the centre of the windchest. The off-note conveyances for the bottom octave of the Bourdon 16ft pipes are fed through the sides of the Box into holes in a block screwed to the outside of the Box. Horizontal feet for the six longest pipes plug both into this block and into the back of the pipes about half way up them. From thence an external wooden wind conveyance travelling down the back of each pipe, feeds the air into the pipe from behind, just below the block. By this method the tops of the pipes are kept slightly lower than the top of the Swell Box. It is strange seeing these large pipes apparently sitting in mid-air without anything holding them up. The smallest six pipes of this Bourdon rank simply stand on this external off-note block.

Some history and interesting observations uncovered during the restoration.

Restorations, such as this, are very much like archaeological digs. The further you look and the more carefully you do it, the more information, however slight, you are likely to uncover Where there has been a major intervention, such as this instrument’s move in 1903, even if it was only 5 metres, you must take even greater care in looking.

I have always been intrigued doing restorations of Hill organs to discover that around 50% of the measurements were exact metric dimensions. This organ contained nearly 90% dimensions in metric figures. I find these facts most curious.

The Pedal Chests and the main passageboard were covered in small indentations, rather like stiletto heel imprints. The worst were removed as best we could from the passageboard until it was realised that these were the marks of hob-nail boots. All remaining indents were preserved as part of the organ’s history and simply painted over.

The Pedal Windchests are laid out in the organ in the reverse order to that normally found i.e. the C side, containing the longest pipe, is situated on the right hand side, thus placing the tallest pipe away from the common view of the organ. It also means that on the side nearest the congregation, the C# side pedal pipes are not as tall, and so the dummy-pipe panels do not have so much height to mask.

The Swell central transverse toeboard was showing signs of splitting, so I carefully used heat and steam to pry the laminations apart in order to replace the blue gasket paper and glue it all up again. As the paper came off in the hot water and steam, I realised that they were printed sheets of something, so laid them aside, to examine them when dry. I discovered that they were time sheets for two of Bevington’s men.

Weekly Time Sheet for Williamson, dated 27 January to 2 February 1877. Organ Job Number 1176

Weekly Time Sheet for Best, dated 7 July to 13 July 1877. Organ Job Number 1176

The time sheets were printed forms and ran from Saturday, Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday. One of the sheets included hours for one day as 12 hrs and another had the hours for the 6 days as 57hrs. The main jobs on the sheets over several days were ‘Bellows’ for Williamson and ‘Bourdon’ for Best.

The insides of the Great and Swell windchests contained perfectly preserved Builder’s Labels with Bevington & Sons name, address, awards won at International Exhibitions, drawings of the medals won; and most importantly the Job Number 1230 and the date of manufacture of the two windchests – June and July 1879.

Further interesting observations were made in several areas. Apart from the Console fittings, no shellac or french- polishing was applied to any part in the organ. This is an immediate difference to Hill, who was liberal with the use of shellac finishes throughout his organs. Bevington’s finish was extremely fine quality sizing ie.very thin hot glue. The various coats were all fine sanded and built up until a very durable finish was obtained. The great advantage, I discovered, was that to clean up all the old dirty parts, you simply washed them quickly in boiling water, which dissolved all the size and then you started again. The resulting finishes were astonishing and no more work than using shellac. Bevington’s original methods have been repeated and the internal finishes speak for themselves.

The rack-boards and the windchests were left untreated in any way, just as Bevington left them. This allows the Honduras Mahogany, already a tropical timber, to breathe in the Sydney climate and not warp.

The lengths gone to, by the builders, to protect the bellows reservoir, feeders and wind trunks, against deterioration in a difficult climate, is extraordinary. The insides of the bellows were first painted with primer. This was then sized and a layer of thick brown paper applied to every surface. To this was glued a layer of heavy canvas material, which in turn was then primed and painted with a final coat of paint. The outsides of the wind-trunks were primed, papered, sized wrapped in canvas, sized and painted. Needless to say, the few cracks in the timber that had opened up over 128 years, through shrinkage, were still almost perfectly sealed with the added protection.

It seems that Bevington thought of everything to make life easier for those installing the organ, by utilising the two thumper rails for the Great and Swell keyboards to set the key height and depth of touch. The rails, when positioned on edge across the key boards, with the off-centre pins resting on the key cheeks, confirmed the bottom of key travel and if turned to the other edge, the top of the key travel.

The Wind Supply